GJIROKASTRAThe city appears in the historical record dating back in 1336 by its Greek name, Αργυρόκαστρο - Argyrokastro, as part of the Byzantine Empire. It became part of the Orthodox Christian diocese of Dryinoupolis and Argyrokastro after the destruction of nearby Adrianoupolis. Gjirokastra later was contested between the Despotate of Epirus and the Albanian clan of John Zenevisi before falling under Ottoman rule for the next five centuries (1417–1913). Throughout the Ottoman era Gjirokastër was officially known in Ottoman Turkish as Ergiri and also Ergiri Kasrı. During the Ottoman period conversions to Islam and an influx of Muslim converts from the surrounding countryside made Gjirokastra go from being an overwhelmingly Christian city in the 16th century into one with a large Muslim population by the early 19th century. Gjirokastra also became a major religious centre for Bektashi Sufism. Taken by the Hellenic Army during the Balkan Wars of 1912–3 on account of its large Greek population, it was eventually incorporated into the newly independent state of Albania in 1913. This proved highly unpopular with the local Greek population, who rebelled; after several months of guerrilla warfare, the short-lived Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was established in 1914 with Gjirokastra as its capital. It was definitively awarded to Albania in 1921. In more recent years, the city witnessed anti-government protests that led to the Albanian civil war of 1997.Along with Muslim and Orthodox Albanians, the city is also home to a substantial Greek minority. Together with Sarandë, the city is considered one of the centers of the Greek community in Albania, and there is a consulate of Greece.

|

|

|

The city appeared for the first time in historical records under its medieval Greek name of Argyrocastron, as mentioned by John VI Kantakouzenos in 1336. The name comes from the Medieval Greek ἀργυρόν (argyron), meaning "silver", and κάστρον (kastron), derived from the Latin castrum, meaning "castle" or "fortress"; thus "silver castle". Byzantine chronicles also used the similar name Argyropolyhni, meaning silvertown. The theory that the city took the name of the Princess Argjiro, a legendary figure about whom 19th-century author Kostas Krystallis wrote a short novel and Ismail Kadare wrote a poem in the 1960s, is considered folk etymology, since the princess is said to have lived later, in the 15th century.The definite Albanian form of the name of city is Gjirokastra, while in the Gheg Albanian dialect it is known as Gjinokastër, both of which derive from the Greek name. During the Ottoman era, the town was known in Turkish as Ergiri.

Antiquity

Middle Ages The city was part of the Despotate of Epirus and was first mentioned by the name Argyrokastro by John VI Kantakouzenos in 1336. That year Argyrokastro was among the cities that remained loyal to the Byzantine Emperor during a local Epirote rebellion in favour to Nikephoros Orsini-Doukas. The first mention of Albanian nomadic groups occurred in the early 14th century, where they were searching for new pasture lands and ravaging settlements in the region. These Albanians had entered the region and took advantage of the situation after the Black death had decimated the local Epirote population. During 1386–1417 it was contested between the Despotate of Epirus and the Albanian clan of John Zenevisi. In 1399 the Greek inhabitants of the city joined the Despot of Epirus, Esau, in his campaign against various Albanian and Aromanian tribesmen. In 1417 it became part of the Ottoman Empire and in 1419 it became the county town of the Sanjak of Albania. During the Albanian Revolt of 1432–36 it was besieged by forces under Thopia Zenevisi, but the rebels were defeated by Ottoman troops led by Turahan Bey. In 1570s local nobles Manthos Papagiannis and Panos Kestolikos, discussed as Greek representative of enslaved Greece and Albania with the head of the Holy League, John of Austria and various other European rulers, the possibility of an anti-Ottoman armed struggle, but this initiative was fruitless. |

|

|

According to Turkish traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the city in 1670, at that time there were 200 houses within the castle, 200 in the Christian eastern neighborhood of Kyçyk Varosh (meaning small neighborhood outside the castle), 150 houses in the Byjyk Varosh (meaning big neighborhood outside the castle), and six additional neighborhoods: Palorto, Vutosh, Dunavat, Manalat, Haxhi Bey, and Memi Bey, extending on eight hills around the castle. According to the traveller, the city had at that time around 2000 houses, eight mosques, three churches, 280 shops, five fountains, and five inns. From the 16th century until the early 19th century Gjirokastra went from being a predominantly Christian city to one with a Muslim majority due to much of the urban population converting to Islam alongside an influx of Muslim converts from the surrounding countryside.

Modern Given its large Greek population, the city was claimed and taken by Greece during the First Balkan War of 1912–1913, following the retreat of the Ottomans from the region. However, it was awarded to Albania under the terms of the Treaty of London of 1913 and the Protocol of Florence of 17 December 1913. This turn of events proved highly unpopular with the local Greek population, and their representatives under Georgios Christakis-Zografos formed the Panepirotic Assembly in Gjirokastra in protest. The Assembly, short of incorporation with Greece, demanded either local autonomy or an international occupation by forces of the Great Powers for the districts of Gjirokastra, Sarandë, and Korçë. In March 1914, the Northern Epirote Declaration of Independence was announced in Gjirokastër and it was confirmed in the Protocol of Corfu. The Republic, however, was short-lived, as Albania collapsed at the beginning of World War I. The Greek military returned in October–November 1914, and again captured Gjirokastra, along with Saranda and Korçë. In April 1916, the territory referred to by Greeks as Northern Epirus, including Gjirokastra, was annexed to Greece. The Paris Peace Conference, 1919 restored the pre-war status quo, essentially upholding the border line decided in the 1913 Protocol of Florence, and the city was again returned to Albanian control. With the incorporation of the city in the Albanian principality the Greek element was deprived of its minority rights. Nevertheless, Gjirokastra, as a multiethnic city, retained its Greek character. In April 1939, Gjirokastra was occupied by Italy following the Italian invasion of Albania. In December 8, 1940, during the Greco-Italian War, the Hellenic Army entered the city and stayed for a five-month period before capitulating to Nazi Germany in April 1941 and returning the city to Italian command. After the capitulation of Italy in the Armistice of Cassibile in September 1943, the city was taken by German forces and eventually returned to Albanian control in 1944. The postwar communist regime developed the city as an industrial and commercial centre. It was elevated to the status of a museum town, as it was the birthplace of the leader of the People's Socialist Republic of Albania, Enver Hoxha, who had been born there in 1908. His house was converted into a museum. The demolition of the monumental statue of the authoritarian leader Enver Hohxa in Gjirokastra by members of the local Greek community in August 1991 marked the end of the one-party state. Gjirokastra suffered severe economic problems following the end of communist rule in 1991. In the spring of 1993, the region of Gjirokastra became a center of open conflict between Greek minority members and the Albanian police. The city was particularly affected by the 1997 collapse of a massive pyramid scheme which destabilised the entire Albanian economy. The city became the focus of a rebellion against the government of Sali Berisha; violent anti-government protests took place which eventually forced Berisha's resignation. On 16 December 1997, Hoxha's house was damaged by unknown attackers, but subsequently restored. |

|

|

CultureCulture 17th-century Ottoman traveller Evliya Çelebi, who visited the city in 1670, described the city in detail. One Sunday, Çelebi heard the sound of a vajtim, the traditional Albanian lament for the dead, performed by a professional mourner. The traveller found the city so noisy that he dubbed Gjirokastra the "city of wailing". The novel Chronicle in Stone by Albanian writer Ismail Kadare tells the history of this city during the Italian and Greek occupation in World War I and II, and expands on the customs of the people of Gjirokastra. At the age of twenty-four, Albanian writer Musine Kokalari wrote an 80-page collection of ten youthful prose tales in her native Gjirokastrian dialect: As my old mother tells me (Albanian: Siç me thotë nënua plakë), Tirana, 1941. The book tells the day-by-day struggles of women of Gjirokastra, and describes the prevailing mores of the region. Gjirokastra, home to both Albanian and Greek polyphonic singing, is also home to the National Folklore Festival that is held every five years. The festival started in 1968 and was most recently held in 2009, its ninth season. The festival takes place on the premises of Gjirokastra Fortress. Gjirokastra is also where the Greek language newspaper Laiko Vima is published. Founded in 1945, it was the only Greek-language printed media allowed during the People's Socialist Republic of Albania.

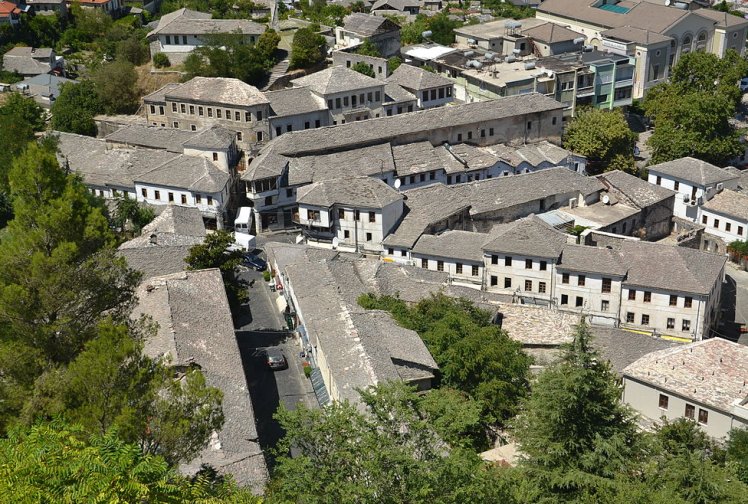

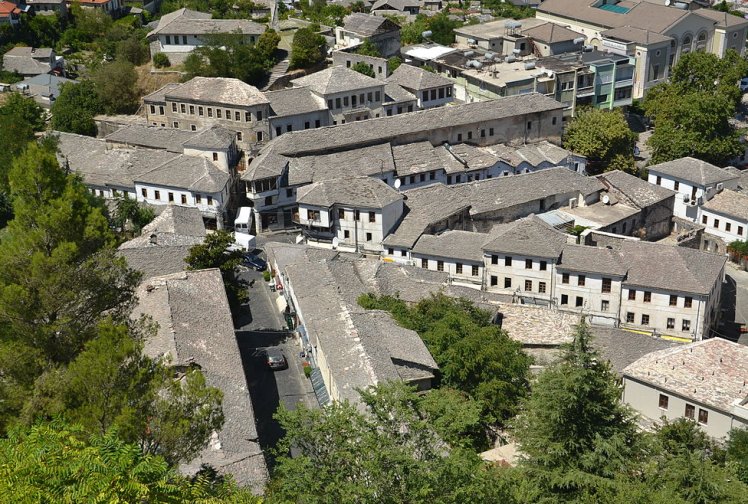

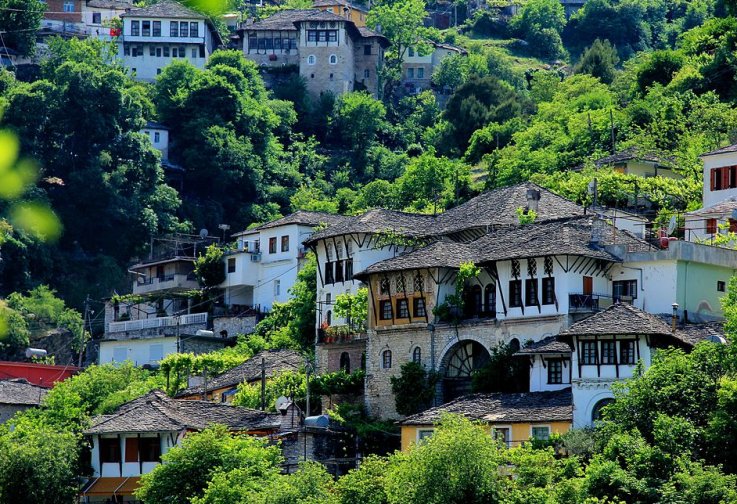

Sights Many houses in Gjirokastra have a distinctive local style that has earned the city the nickname "City of Stone", because most of the old houses have roofs covered with flat dressed stones. A very similar style can be seen in the Pelion district of Greece. The city, along with Berat, was among the few Albanian cities preserved in the 1960s and 1970s from modernizing building programs. Both cities gained the status of "museum town" and are UNESCO World Heritage sites.

|

|

|

Gjirokastra Fortress dominates the town and overlooks the strategically important route along the river valley. It is open to visitors and contains a military museum featuring captured artillery and memorabilia of the Communist resistance against German occupation, as well as a captured United States Air Force plane, to commemorate the Communist regime's struggle against the imperialist powers.

Additions were built during the 19th and 20th centuries by Ali Pasha of Ioannina and the government of King Zog I of Albania. Today it possesses five towers and houses a clock tower, a church, water fountains, horse stables, and many more amenities. The northern part of the castle was turned into a prison by Zog's government and housed political prisoners during the communist regime. Gjirokastra features an old Ottoman bazaar which was originally built in the 17th century; it was rebuilt in the 19th century after a fire. There are more than 500 homes preserved as "cultural monuments" in Gjirokastra today. The Gjirokastra Mosque, built in 1757, dominates the bazaar:

When the town was first proposed for inclusion on the World Heritage list in 1988, International Council on Monuments and Sites experts were nonplussed by a number of modern constructions which detracted from the old town's appearance. The historic core of Gjirokastra was finally inscribed in 2005, 15 years after its original nomination. The Ethnographic Museum was founded in 1966 and used as the Anti-Fascist Museum until 1991. It is a replica of a typical house for Gjirokastra built in 1966, located on the site of Enver Hoxha's burnt-down birthplace:

|