KOMOTINI

Komotini (Greek: Κομοτηνή, Turkish: Gümülcine) is a city in the region of East Macedonia and Thrace, northeastern Greece. It is the capital of the Rhodope. It was the administrative centre of the Rhodope-Evros super-prefecture until its abolition in 2010, by the Kallikratis Plan. The city is home to the Democritus University of Thrace, founded in 1973. Komotini is home to a sizeable Turkish speaking Muslim minority. They were excluded from the 1923 population exchange. According to the 2021 census, Komotini has population of 65,107 citizens.

Built at the northern part of the plain bearing the same name, Komotini is one of the main administrative, financial and cultural centers of northeastern Greece and also a major agricultural and breeding center of the area. It is also a significant transport interchange, located 795 km NE of Athens and 281 km NE of Thessaloniki. The presence of the Democritus University of Thrace makes Komotini the home of thousands of Greek and international students and this, combined with an eclectic mix of Western and Oriental elements in the city's daily life, have made it an increasingly attractive tourist destination.

|

|

Old Town of Komotini Ermou Street Clock Tower

History

Antiquity

Komotini has existed as a settlement since the 2nd century AD. That is confirmed by archaeological finds of that era up until the 4th century. It is also confirmed by an inscription on the ruins of the 4th-century Byzantine wall, that are visible at various sites in the city, which reads "Theodosiou Ktisma" = Building of Theodosius. The inscription was discovered by the Komotini-born Prof. Stilponas Kyriakidis and the then mayor Sofoklis Komninos. It is said that the settlement originates from the 5th century and is linked to the daughter of the painter Parrasios from Maroneia. During the Roman age it was one of several fortresses along the Via Egnatia highway which existed in the Thrace area. Probably it is to be identified with the Roman station Breierophara (a Thracian toponym from bre (=fortress) + iero (= holy) + phara=para (=pass). The most important city of that period was neighbouring Maximianopolis, former Thracian Porsulis or Paesoulae, which was renamed to Mosynopolis in the 9th century. Komotini was a Via Egnatia hub on its northern route through the Nymphaea Pass which led to the Ardas Valley, Philippopolis (modern Plovdiv) and Byzantine Berroe (modern Stara Zagora).

Byzantine era

The city's history is closely connected with that of Via Egnatia, the Roman trunk road which connected Dyrrhachium with Constantinople. The Roman emperor Theodosius I built a small rectilinear fortress on the road at a junction with a route leading north across the Rhodope Mountains toward Philippopolis. During the Byzantine period, the city belonged to the Theme of Macedonia, whilst from the 11th century it could be found within the newly founded theme of Boleron. For most of its early existence the settlement was overshadowed by the larger town of Mosynopolis to the west, and by the end of the 12th century, the place had been completely abandoned.

The current settlement dates to 1207, when, following the destruction of Mosynopolis by the Bulgarian tsar Kaloyan, the remnant population fled and established themselves within the walls of the abandoned fortress. Since then the population had been increasing continuously until it became an important town within the area. In 1331 John Kantakouzenos referred to her as Koumoutzina in his account of the Byzantine civil war of 1321–1328. In 1332 Andronikos III Palaiologos set camp in Komotini to face Umur Bey of Smyrna at the Panagia village close to the Panagia Vathirryakos (Fatirgiaka) monastery. However, Umur departed without a battle. In 1341 the historian Nikephoros Phokas referred to the town with its current name. In 1343, during the civil war between John VI Kantakouzenos and John V Palaiologos, Komotini along with the neighbouring forts of Asomatos, Paradimi, Kranovouni and Stylario joined Kantakouzenos' side. John VI Kantakouzenos escaped to Komotini to survive from a battle with the army of the Bulgarian brigand Momchil near the already ruined Mosynopolis.

|

|

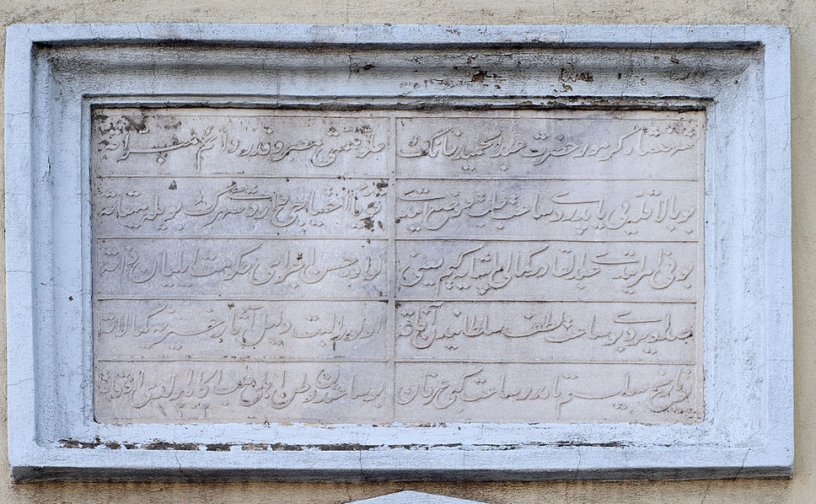

Byzantine fortress Inscription in Ottoman script on the clock tower

Ottoman era

The city was conquered by the Ottoman Empire between 1361 and 1362/63, apparently by Gazi Evrenos Bey. Its conquest is placed after the fall of Philippopolis and Stara Zagora, but before the Ottoman capture of Pegae. Already before that, it was called in Turkish as Gümülcine, a version of the demotic Greek form of the city's name, Koumoutsinas. This remained the city's name throughout the Ottoman period (ca. 1361–1912) and continues as its modern Turkish-language name today.

The city continued to be an important hub connecting the capital city of Constantinople with the European part of the Empire, and grew accordingly. Many monuments in the city today date to this era. Many local Greek families fled at that time to Epirus and founded the Koumoutzades village (modern Ammotopos, Arta). Even there they were persecuted by the Ottomans and some of them found refuge in Tropaia of Gortynia. The bond between the inhabitants of Komotini, Ammotopos and Tropaia exists to this day.

In the first two decades after its conquest, until 1383, the city was the seat of a frontier march (uç) under Evrenos, confronting the Serbian territories of Macedonia. The walled city continued to be inhabited by locals, Gazi Evrenos also brought in Turkish settlers to the countryside around the town to stop any riots. During the prevailingly Ottoman rule of the area, it appears that the region was largely supported, and subsequent Ottoman censuses show that Muslim Turks quickly became the dominant element in the rural districts around the city. Evrenos also invested in the city as building camiiye (small mosque), an imaret, bath, and shops outside the city walls, establishing a waqf that according to Machiel Kiel became the "nucleus of Islamic life in Western Thrace". The 16th-century geographer Mehmed-i Ashik also mentions a hostel (imaret) built by Evrenos.

In the 1519 census, the city numbered 393 Muslim households and 197 single (unmarried or widowed) Muslims, 42 Christian households and 14 single Christians, and 19 Jewish households and 5 single Jews, in total ca. 2,500 people. In the 1530 census, the 17 Turkish-named neighbourhoods (mahalle) are mentioned, as well as the existence of one Friday mosque, 16 masjids, 4 zawiyas, 4 schools, and a single church (in the walled city). Nevertheless, the French traveller Pierre Bellon du Mans, who visited the city in 1548, stated that "the city is inhabited by a few Greeks and majority Turks". In the 1600s, the town was graced by new buildings—a small Friday mosque, a double bath, a mekteb, a madrasah, and an imaret—by the defterdar Ekmekcizade Ahmed Pasha, who sponsored numerous such works throughout Thrace. Ahmed's mosque, the Yeni Mosque, which survives to this day, is the only structure in Greece to feature Iznik tiles from the 1580s, the zenith of the Iznik potters' art. When the traveller Evliya Çelebi visited the town in 1667/68, he found "4,000 prosperous, stone-built houses"—likely an exaggeration—in 16 mahalles, with 5 main mosques, 11 masjids, 2 imarets, 2 baths, 5 madrasahs, 7 mektebs, 17 caravanserais, and 400 shops.

The town suffered greatly from repeated plague epidemics, which led to entire villages being abandoned, but recovered in the 19th century. During the Greek War of Independence Komotini's inhabitants contributed substantially with Ioannikios (later bishop), Aggelis Kirzalis and Captain Stavros Kobenos (members of the Filiki Eteria organisation). During the following decades Komotini progressed financially due to the processing and trade of tobacco.

The 19th century saw the city expand and considerable architectural activity, with the renovation of old and the construction of new buildings. Both the Yeni Mosque and Evrenos' original masjid, the Eski Mosque, were enlarged by the addition of spacious prayer halls, while Sultan Abdulhamid II erected a clock tower and a madrasah. During his reign, the town became a station in the railway linking Constantinople with Salonica. By the 1880s, the city, capital of the homonymous sanjak in the Edirne Vilayet, boasted 13,560 inhabitants, 10 Friday mosques, 15 masjids, 2 Greek and one Armenian church, a synagogue, 4 madrasahs, two higher schools, ten mektebs, and various other Christian and Jewish schools.

Balkan Wars and World War I

During the First Balkan War, Bulgarian forces captured the city, only to surrender it to the Greek army during the Second Balkan War on July 14, 1913.

In the aftermath of the Second Balkan War, it became briefly the capital of the short-lived Provisional Government of Western Thrace, but the Treaty of Bucharest, however, handed the city back to Bulgaria. The city was part of Bulgaria until the end of World War I. During this period, the city had the Bulgarian name Гюмюрджина Gyumyurdžina. In 1919 after the end of WWI, with the Treaty of Neuilly, Komotini was handed to Greece, along with the rest of Western Thrace.

Demographics

The population is quite multilingual for a city of its size and it is made up of local Greeks, Greek refugees from Asia Minor and East Thrace, Muslim population of Turkish, Pomak, Greek and Roma origins, descendants of refugees who survived the Armenian genocide, and Pontic Greeks from north-eastern Anatolia and the regions of the former Soviet Union (mainly Georgia, Armenia, Russia and Kazakhstan).

The Muslim population of Western Thrace dates to the Ottoman period, and unlike the Muslim population in other regions of Greece were exempted from the 1922-23 Greek-Turkish population exchange following the Treaty of Lausanne.

Modern Komotini

|

|

The old courthouse Greek School of Nestor Tsanaklis

Komotini is, nowadays, a thriving commercial and administrative centre. It is heavily centralised with the majority of commerce and services based around the historical core of the city. Getting around on foot is therefore very practical. However, traffic can be remarkably heavy due to the daily commute. In the past, the Trelohimaros river used to flow through the city and divide it into two parts. In the 1970s, after repeated flooding episodes the river was eventually diverted and flows on the east of the city, while its former bed has been replaced by the main avenues of the city, such as the Orfeos Street.

|

|

Statue of Constantinos Karatheodoris Church of St Barbara

Heart of the City

At the heart of the city lie the evergreen Municipal Central Park and the 15 m-high WW2 Heroes' Memorial, locally known as 'The Sword'. The revamped Central square or Plateia Irinis (Square of Peace) is the focus of a vibrant nightlife boosted by the huge number of students living in the city. The Old commercial centre is very popular with tourists as it houses traditional shops and workshops that have long vanished from other Greek cities. In addition, in the northwestern outskirts of the city (Nea Mosinoupoli) locals and tourists alike flock into a modern shopping plaza: Kosmopolis Park, which houses department stores, shops, supermarkets, a cinema complex, cafés and restaurants. The area stretching from Kosmopolis to Ifaistos is gradually becoming a retail destination in its own right.

Culture and Entertainment

Komotini began life as a Byzantine Fortress built by the Emperor Theodosius in the 4th century AD. The ruins of this quadrangular structure can still be found NW of the central square. Komotini has several museums including the Archaeological, Byzantine and Folklore museums. SW of the central square one can find the Open-air Municipal Theatre, which hosts many cultural shows and events such as the cultural summer (πολιτιστικό καλοκαίρι = politistiko kalokairi). There is a Regional Theatre (DIPETHE) whose company produces many plays all year round. 6 kilometres (4 miles) NE of Komotini is the Nymfaia forest. It has recreational facilities which comprise trails, courts, playgrounds and space for environmental studies. The forest is divided by a paved road which leads to the ruins of yet another Byzantine fortress and the historical (WWII) fort of Nymfaia.

Jewish Community

|

|

Holocaust Memorial The Imaret, today the ecclesiastical museum

Writings in the area of ancient Maroneia confirm the presence of Jews in the area. In the 16th century the Jewish community of Komotini consisted of Sephardite Jews who were textile and wool merchants. Many of the Jews had come to Komotini as immigrants from Edirne and Thessaloniki. The Jewish community was concentrated within the ancient walls of the city and was expanded after 1896 to the west, along Makavaion street (renamed Karaoli), where the Jewish school and Jewish club were located. The synagogue Beth El was built in the 19th century within the citadel and was enlarged in stages, as late as in 1914. The synagogue was used as a stable during WWII, and later stood abandoned for many years. After the roof collapsed in 1993, the synagogue was demolished in 1994. In 1900 there were 1,200 Jews. In 1910 the Alliance Israelite Universelle School started functioning. Greek, French and Hebrew were taught in the school. In 1912–13 many Jews moved to larger cities such as Thessaloniki and Istanbul. After the liberation of Komotini (May 1920) the Israelite community of Komotini had a Cultural Club and Charity organisations. During the Bulgarian administration, the Bulgarians (Nazi allies) arrested 863 Jews and sent them to the concentration camp of Treblinka where they were exterminated (28 survived the Holocaust). In 1958 the Israelite community was dissolved due to lack of members. In 2004 the municipality of Komotini created a memorial (southern entrance of Central Park) for the victims of the Holocaust.

|

|

Armenian Church of St. Gregory Museum Karatheodoris

|

|

May 14, 1920: Liberation from Bulgarian occupation Historic tobacco warehouse

|

|

The Yeni Mosque and the Clock Tower Eski Mosque - 17th century

|

|

Septimius Severus, Archaeological Museum Ethnographic Museum